As it is now almost Christmas, it is sobering to remind

that the date this feast was only fixed somewhere at the end of the 4th

century. The Bible tells us nothing about the date and the Gospel of Marc - the

oldest gospel – has nothing to say at all about the birth of Jesus. Under

popular pressure and theological reflections, such as the rise of the prominence

of Mary, a date was fixed, which conveniently was around the same date as some

heathen feasts like the Saturnalia. This is of course more than coincidence: though

it would be nonsense to claim that it was under the direct influence of

Mithraism, the connection between Christ and light was easily made and had its

foundation in the Gospel of John. Indeed, there are pictures of Christ

resembling the sun-god Apollo; an iconographical resemblance, not a theological.

Possibly Ambrose of Milan (340 – 397) introduced the date

of the birth of Jesus in his diocese – Rome had already preceded. It is

tempting to think that the following hymn was written for that occasion, but as

with the exact historical circumstances of fixing the date of Christmas, this

too would overstretch our sources.

Ambrosius, Intende,

qui regis Israel. (By far not all biblical parallels have been noted.)

1 Intende, qui

regis Israel,

super Cherubim

qui sedes, qui sedes super

appare Ephraem coram, excita one of the tribes of Israel

potentiam tuam

et veni! For the first stanza cf. Psalm

79/80

intendo intendi

intentum: to give attention

appareo apparui:

to appear

coram: before,

in front of

excito (-are): bring out, rouse

2 Veni, redemptor gentium, note the repeating veni

ostende partum

virginis,

miretur omne saeculum, saeculum: both world and age

talis decet

partus deo. (that)

such (a low) birth

decet here with dative

ostendo ostendi

ostentum: to show

partus –us (m.): birth, delivery

3 Non ex

virili semine,

sed mystico spiramine spiramen = Holy Ghost

verbum dei

factum est caro cf. John

1.14

fructusque

ventris floruit.

4 Alvus

tumescit virginis,

claustrum pudoris permanet, the barrier of chastity remains (closed)

vexilla

virtutum micant,

versatur in templo deus. in templo: i.e.

the belly of Mary

alvus (m./f.) :

belly

tumesco tumui:

to (begin to) swell

vexillum:

banner, flag, standard

mico (-are): to vibrate, shine

versor versatus:

to dwell

5 Procedat e thalamo suo,

pudoris aula regia, the

royal court of chastity (ablative!) = Mary

geminae gigas substantiae, i.e. His divine and human nature

alacris occurrat viam. may

he enter the road (of salvation)

procedo processi

(-ere): to come/go forth

thalamus:

chamber

gigas gigantis

(m.): giant

alacris = alacer: quick, eager, happy

6 Egressus eius a patre, note the use of e

(out) and re (return)

regressus eius ad patrem,

excursus usque ad inferos, to those below, i.e. hell

recursus ad sedem dei.

7 Aequalis aeterno patri, vocative:

you who are equal etc.

carnis tropaeo accingere, accingere: inf. pro imp.

infirma nostri corporis infirma

firmans: making strong the weak things etc.

virtute firmans perpeti.

tropaeum: trophy

perpetuus: eternal (perpeti

= perpetii)

8 Praesepe iam

fulget tuum

lumenque nox

spirat novum,

quod nulla nox

interpolet

fideque iugi luceat.

praesepe –is (n.):

stable

fulgeo fulsi (-ere): to flash, glitter

interpolo (-are): to alter

iugis –e: continual,

perpetual

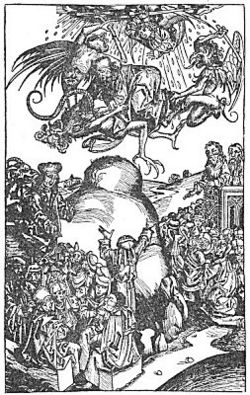

Picture from de Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague.

Performance by Capella Antiqua München, conductor Konrad

Ruhland.

Translation by Peter G. Walsh with Christopher Husch (One

Hundred Latin Hymns, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 18, 2012)

Give ear, O

king of Israel,

seated above

the Cherubim,

appear before

Ephraim’s face,

stir up thy

mightiness, and come.

Redeemer of the

Gentiles, come;

show forth the

birth from virgin’s womb;

let every age

show wonderment;

such birth is

fitting for our God.

Not issuing

from husband’s seed,

but from the

Spirit’s mystic breath,

God’s Word was

fashioned into flesh,

and thrived as

fruit of Mary’s womb.

The virgin’s

womb begins to swell;

her maidenhead

remains intact:

the banner of

her virtues gleam;

God in his

temple lives and stirs.

From his

chamber let him come forth,

the royal court

of chastity,

as giant of his

twin natures

eager to hasten

on his way.

First from the

Father he set forth,

then to his

Father he returns;

he sallies to

the realms below,

then journeys

back to God’s abode.

You are the

eternal Father’s peer;

gird on your

trophy of the flesh,

and strengthen

with your constant power

the frailties

of our bodies’ frame.

Your manger now

is all aglow,

the night

breathes forth a light unknown;

a light that

never night may shroud,

and that shall

gleam with constant faith.